The flavour is perfect, the ingredients are all cooked to perfection, but that sauce is just too thin. Sure, you could reduce it, but you’d be concentrating the flavour, overcooking all the other bits and throwing the sauce:contents ratio all off. The only solution is to use some kind of thickening agent, but what?

This post covers four basic techniques for thickening sauces using the three most common ingredients: flour, cornflour, arrowroot. I’m going to tell you the what, where and why. If you’ve come here for an easy reading recipe, you might want to take a look at my recipe file because this post is crammed full of information.

Welcome to the 101 guide to thickening sauces, soups and stews.

Let’s begin with the most basic:

Thickening Sauces with Plain Flour

Plain flour, or all purpose flour is available everywhere and most people have some in their cupboards so it’s handy to know how to thicken sauces properly with this household staple.

How it thickens:

Gluten flours mainly consist of starch, in fact 75% of the average plain flour is starch. These starch molecules absorb water and under the right amount of heat swell up and burst, releasing a gel like substance which is what makes it such a good thickener. It’s an irreversible process, once the water has bonded with the flour and gelatinized, there’s no going back.

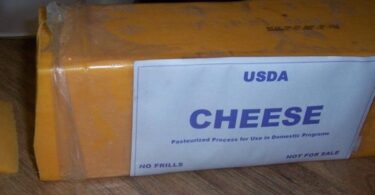

In the UK it’s against the law to use bleaching agents in flour, which is why the flour above (middle spoon) looks so cream compared to the cornflour and arrowroot on either side. I thought I’d point that out for my US readers who will need to use more flour if using a bleached variety due to the gluten that the process removes.

Note that if you intend on using wholewheat flour rather than plain, it has less starch per tablespoon than plain white flour so, you’ll need to add slightly more.

Texture, appearance, flavour:

Flour gives a velvety, creamy mouthfeel and adds more body to sauces so it’s ideal for rich or cream based sauces like my creamy chicken soup. Flour, if uncooked, can add an unpleasant raw flavour to sauces but once cooked (following the instructions below) it is nutty and rich.

How to and how much?

The general rule is 2 tsp of flour to thicken 1 litre of liquid, but this of course varies depending on how thick you’d like the sauce to be and how thick it is already.

The easiest way to thicken a sauce with plain flour is to make a flour slurry. Simply mix equal parts of flour and cold water in a cup and when smooth, stir in to the sauce. Bring the contents to a simmer for 5 minutes to cook away the raw flour taste. By mixing the flour with cold water first, it ensures the starch granules are separated so they’re less likely to link together and form clumps when they meet the hot liquid.

The next option is a Beure marnie; equal parts butter and flour, kneaded in to a dough. It’s ideal for thickening small amounts of liquid, like a pan sauce. Add a small amount to a hot pan of sauce and whisk until combined. Simmer for 3 minutes to cook the flour and thicken.

If you’re making a recipe that you’ve previously found to be too thin, you can start it off with a roux or the dusting method to thicken the sauce.

A Roux is made of equal parts fat and flour, just like the beure marnie, apart from it is cooked first before the sauce is started. Simply add the chosen fat or oil to a saucepan until melted then add the flour, stirring to combine and allowing to turn a light golden colour. It’s important to remember that this colour will be transferred to the final sauce so it isn’t suitable for all recipes. You can of course cook a roux past that golden phase to achieve deeper colour in your sauce but the over cooked flour loses its thickening ability. Once the roux is made, add the liquid and continue with the recipe as normal, adding a 3 minute simmer to thicken.

You’ll be familiar with the dusting method if you’ve made casseroles and stews. It involves tossing the meat, veggies or other ingredients in flour before cooking. Essentially this does exactly the same as a roux; the oil in the pan and fat from the meat (or what you’ve added) combine and the flour is cooked. I personally think this method is easier than making a roux. You’re less likely to burn the flour and it cuts the extra step out.

It’s worth noting that neither the slurry nor the dusting method involve added fats so may be your choice of thickening method if you’re watching your fat intake.

Most sauces and casseroles thickened with flour will freeze and reheat well. The sauce will become more opaque and solid as it cools but should return to the original consistency once reheated.